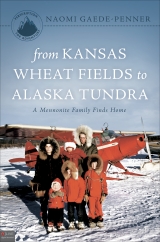

Beginning in 1943, my Gaede grandparents collected letters my parents wrote. After my parents died, I discovered this archive. As I opened the time-worn envelopes with quaint 4-cent stamps and read their fragile, faded letters, I came upon the phrase, "Save these letters—we may write a book someday." In 1991, my father and I had published a book of his adventures, Prescription for Adventure: Bush Pilot Doctor. Since that time, I've been asked for more information. "What about your Mom?" "What was it like for you?" This book begins to answer some of those questions.

In 1961, our parents, Elmer and Ruby Gaede (Gay-dee), put down roots on the Kenai Peninsula in Alaska. Our 80 acres quickly became known as the Gaede-80. Back then, it wasn't as though you could just purchase the property, gather up some boards, nails, and shingles, construct a house and call it home. Nope! This was homesteading. There were rules. The land had to be proved up. Those two simple sounding words meant sweat, backaches and blisters—and freezing and loneliness, too.

Elmer Homesteading

Those homesteading seeds did not sprout for many years. Dad and Mom had always expected to be dairy farmers in Kansas. In fact, Mom's first prize in life was for milking a cow. I guess that on Dad's way from some cornfield, he took a wrong turn. Instead of walking into a barn he found himself at Kansas University Medical School, in Lawrence—anticipating a missionary's life in South America.

Amidst Dad's classes of anatomy, physiology, and physical diagnosis, I came along. Sixteen months later Ruth showed up.

Life was good, but in the early 1950s good was difficult. Trips to Mom's home place supplemented our meager larder. Her parents, Solomon and Bertha Leppke, farmed outside Peabody—a town in Central Kansas where the railroad had once ended, dumping out Mennonites and other immigrants onto the prairie to start new lives and struggle to eek out a living from the stubborn soil. My Mennonite great-grandparents had arrived on one of those trains. They brought with them Turkey Red Wheat, courage, resourcefulness, and the love of land.

When Mom was in the hospital delivering Mark, her roommate was a chief's wife from St. Lawrence Island. Mom immediately took a liking to this dear Eskimo woman who stood only four-feet tall. Long black braids and bangs framed the black tribal marks on her forehead and chin. Fourteen pregnancies had only produced three living children; all other babies were premature and stillborn. This time, in hopes for survival of her child, the chief had sent her to the Anchorage Native hospital.

Naomi, Ruth, Elmer — First Winter in Anchorage

The blizzard packed snow against our house, obscuring the windows and banking it into a hard-packed hill up to the eaves. The lights inside the house flickered and the furnace back-fired. When our roof creaked, Dad walked up the south-side snow hill to shovel off the several feet of snow. Ruth and I skied down the wind-smoothed surface. Then the thermometer dropped to 30 below. Water lines were freezing all over town so Mom and Dad left our faucets dripping slowly all night long. The 1947 Chevy groaned in protest. Dad bought an engine block heater that he plugged in each morning while he ate breakfast and he mixed Ban-Ice into the gasoline to absorb moisture in the fuel system. When we drove, Dad didn't use the car heater—he said it drained too much heat from the defroster. The car never thawed, either inside or out. Dad chiseled ice from the floorboards.

Bumpy blobs of ice flowed down the center of the river while a ledge formed along the water's edges. One morning, we drew back the drapes to a palpable stillness. The flow in the center had frozen shut. The river didn't freeze smooth like an ice skating rink or a lake. The powerful current smashed huge wedges together, some rising perpendicular as frozen masses pushed from behind. Our world had changed overnight. Just as people live with the constants of ocean tides, afternoon mountain rain showers and cows following single-file to a barn at milking time, so, we expected to see the reliable backdrop of moving water as we went about our lives. It was as if we'd awakened on a new planet.

* * * * * * * * *

Mom had come up with the idea to add another child to our family. Her conversation with Dad happened something like this:

- "Ruth and Naomi have each other. Mark has no one."

- "Okay?" Dad looked at her quizzically. He'd studied human reproduction and they'd already produced three children. This didn't seem complicated.

- "I will not get pregnant again," she said. "You will have this next baby."

Dad wrote his parents:

One doctor is on vacation. The load is impossible. We make rounds

every morning on our 20-28 patients and then usually some kind of

surgery. In the afternoon, we generally see 50-100 patients. We are

on call every night. I see more fractures in one week than I did at

our previous assignment.

* * * * * * * * *

Mom was tangling in laundry on the clothes line, her fingers frozen in the wind. She looked momentarily across the desolate hills and saw a red speck disappearing over the horizon. "Elmer! There's Mark!" she pointed.

It was a land of milk and honey. Flowers bloomed unbidden along the roadsides and plump fruit hung heavily on trees. Now we lived in a Dick-Jane-and-Sally neighborhood.

The fall rain continued. The basement flooded. Mom and Dad hauled buckets of water up the stairs The interior walls dripped and washed clothes hung inside to dry — didn't dry. Ruth and I snuggled back-to-back in our double-bed with our flannel pajamas. In the morning, we'd usually find our blankets frozen to the damp purple walls. But, we had it pretty well off compared to people living in the one-room plywood shanties across the river.

March 18, 1963

Our main activities center around our 80 acre

homestead. You should see us in our ragged army clothes when we work. A

lot of snow has settled on the tree branches. We usually get quite wet

and we tear our clothes or burn many small holes in the clothes as we

work so near fires we make with the brush trimmed from the trees. I

bought a new McCullough chainsaw and it handles so easily that even Ruby

can use it at times. We are just completing a clearing for our runway

which will be 120 feet wide and about 2,400 feet long.

Naomi in the white jacket. Mark in the red parka.

Our California cousins loved this Alaskan hunting . . . the beaten

path petered out to no trail at all. Gray skies began to drizzle.

We entered wet, thick four-foot-high grass. Harold broke the trail,

pushing the grass aside until he couldn't swim through it

anymore.

"Elmer, I can't do this. I'm just too tired," he gasped.

"Okay, you take the rear and carry the gun," Dad instructed.

"You know this is bear country. You'll hear a woof, like a dog.

Be ready to shoot."

Mark Gaede by his Super Cub.

We hadn't tagged along after our parents without turning out somewhat like them. And, finding home wasn't the end — for any of us. The adventures didn't fade away when we set down roots on the homestead. Not a chance. The Gaede Eighty became the launching pad for more escapades, challenges, and adventures. We were all just beginning.